"Don't Build Me a Stupa": The Legacy of Thich Nhat Hanh

Now that Thich Nhat Hanh (aka Thầy or “teacher”) has died, I’ve been reflecting again on this great teacher and his legacy. Notably, he asked his students not to build him a stupa - a site of veneration - however, as you may have also witnessed, the social media landscape is filled with stupas!

Now that Thich Nhat Hanh (aka Thầy or “teacher”) has died, I’ve been reflecting again on this great teacher and his legacy. Notably, he asked his students not to build him a stupa - a site of veneration - however, as you may have also witnessed, the social media landscape is filled with stupas!

It’s a normal part of the grieving process, of course. At the same time, it captures how Thầy could serve as the object of people’s “perfect guru” projections. One post I saw said, “Our wonderful great teacher has now ascended in glory.”

"Ascended in glory"? Who died, Thầy or Jesus Christ?

As for me, I’d like to honor Thầy by not building a stupa for him. So in this post, I’ll give a more balanced view of the impact of Thầy’s teaching.

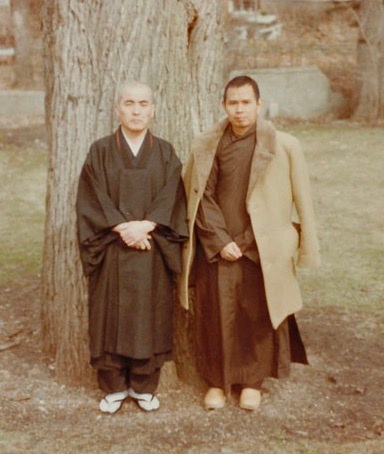

First, though, let me tell you about the first time I met Thầy (see the attached photo). In March, 1983, a then unknown Vietnamese monk came to the Minnesota Zen Center to give a series of talks at the invitation of the local Vietnamese Buddhists. They had contacted us to see if they could use our space for a visiting monk’s teaching. A bunch of Katagiri Rōshi’s students, as well as Rōshi, attended the series out of curiosity. We were soon gazing at each other wondering, “Who the heck is this guy?”

It became clear during this weekend series that Thầy was an unusually gifted teacher, expressing difficult aspects of Buddha’s teaching with an ease and simplicity that was unlike anyone I’d heard at the time - or since. He had a keen mind and was also unusually adept at reading the room and pacing his message. In addition, Thầy had a powerful presence - gentle, profound, and sincere.

Even back then, his message was about mindfully enjoying the breath and all of this life. He also seamlessly stressed the importance of practicing peace and nonviolence - another of his major themes throughout his career and another way that he impacted the landscape of dharma discourse in the West. Given the success of his teaching and its impact on contemporary dharma narrative, it is now hard to convey how radical both themes seemed at the time.

I remember clearly that at the end of this series, Thầy turned to Katagiri Rōshi and asked him to say a few words. With Rōshi’s characteristic scowl (when he was deadly serious), his voice gruff and surprisingly shaky, he said, “Dogen Zenji say, ‘Study buddhadharma for the sake of buddhadharma.’ That is all.”

Given that Thầy had emphasized the physical and emotional benefits of mindfulness during this series, I took Rōshi’s comment as adding a different point of view or even a challenge to Thầy’s message. The contrast between them in that moment was stark.

Yet Thầy and Rōshi hit it off like few people that I’d seen pass through the Zen Center. They seemed to completely understand and respect each other both in terms of the dharma and in the difficulty of the refugee lives they were both leading. They also both had experienced the devastating trauma of war and I believe that they both could relax in the presence of another survivor.

With Rōshi’s approval, I went on to attend several retreats that Thầy led in the US over the next six years, culminating with a month in France at Plum Village. At the time, I knew I’d be doing at least a year retreat somewhere starting the following year. I’d already done about 500 days of sesshin, ~20 nonresidential 100 day practice periods, and a handful of residential practice periods - all in Rōshi’s Sōtō style. It was time to see the dharma from a different perspective. I knew that Rōshi wanted me to go to a monastery that we’d visited in Japan, but at the time, I thought that perhaps I’d see if I could convince Rōshi to give me permission to go to Plum Village instead.

The month at Plum Village was a delight. In '89, there were only ~80 students (including the Vietnamese in the lower hamlet) and so a very small group compared to what was coming. However, even in retreat, the sitting schedule was light and it was difficult to have any individual time with Thầy. The years of personal access that I’d had to Katagiri Rōshi in and out of sesshin had marked me. So although I learned a lot at Plum Village, I didn’t find their intensity of practice, their wholeheartedness, to be what I’d experienced with Rōshi. What gave me energy for the way was not encouraged at Plum Village.

So I left Plum Village and ended my half-dozen years of doing some study with Thầy while I was also training closely with Katagiri Rōshi.

Now, more than thirty years later, when I look at Thầy’s legacy, I see how positively he has impacted the practice of the buddhadharma. The titles of two of his early books, The Miracle of Mindfulness and Peace is Every Step say at least 80% of it.

And with any teaspoon of medicine there is also a teaspoon of potential disease. Below are a few drops of disease that have more to do with the impacts of Thầy’s teaching and less to do with Thầy himself or what he actually taught:

1. Thầy’s teaching often seems to be understood as saying that mindfulness of divided mind is awakening. This conflation of nonawakening with awakening plays well with our modern propensity to look for an easy-going way, but in no way does it tap out the depths of absorption and insight that are available within the buddhadharma.

2. I worry also about the long term impacts of the “perfect guru” projection that Thầy elicited. Most of the people that are posting most of the things I’m seeing on social media did not have a personal relationship with Thầy and yet attest to him being a perfectly awakened bodhisattva. There are people who have a natural charisma that is unrelated to dharma realizations and it is easy to mistake the two. Situations that are supported by projections like this seldom end well.

Let me be clear - in my experience, Thầy was a wonderfully sweet man and fully dedicated Buddhist monk. It was a great gift to have spent some of my life studying with him. But he was not perfect. He was known by those in his inner circle as having a quick and hot temper. I saw myself that he could be very rough when giving feedback to students. And as with any human teacher, there are students of Thầy that I’ve spoken with who reported having issues with how he treated them that seemed legitimate to me. One couple had their institutional and financial legs kicked out from under them without any notice. I don’t know what Thầy’s perspective was, of course, and just heard their side of this big dispute in the 90’s. The point is, Thầy like other mortals was a work in progress.

3. Thầy is often quoted as saying that the next buddha will be the community. That’s never rung true for me and now I see it embraced by many to justify a one-sided horizontalism in dharma communities that does not serve students settling deeply into either absorption or awakening. And the authentic dharma cannot continue without these elements. For 2500 years we’ve had three jewels but now just one? Because we’re so special? Nah. The Buddha of the Pali Canon is likewise often quoted as saying that the sangha is the whole of the holy life. What the Buddha said, though, is that the kalyanamitra is the whole of the holy life. Kalyanamitra actually means “good friend,” “spiritual guide,” or “dharma mentor.” The Buddha of the Pail Canon sometimes referred to himself as a kalyanamitra.

So to confuse kalyanamitra with anybody who happens to wander into a Zen Center on any given day is just naive, sloppy, and not the intent of the Buddha. And as Tetsugan Sensei has pointed out, it is pretty darn ironic - and an internal contradiction - that people are heard saying, “Thich Nhat Hanh says that the community will be the next Buddha” - they quote a teacher to whom they give considerable dharma authority as saying the community will be the next dharma authority. It may not be a coincidence that this is so supportive of the identity center for many students today.

Please receive this as my contribution to my old teacher’s no-stupa.