Problems With The Platform Sutra: Dogen

...if you have a problem with the buddhadharma and don't even consider the possibility that it might be your personal problem, you really aren't in that moment studying the buddhadharma.

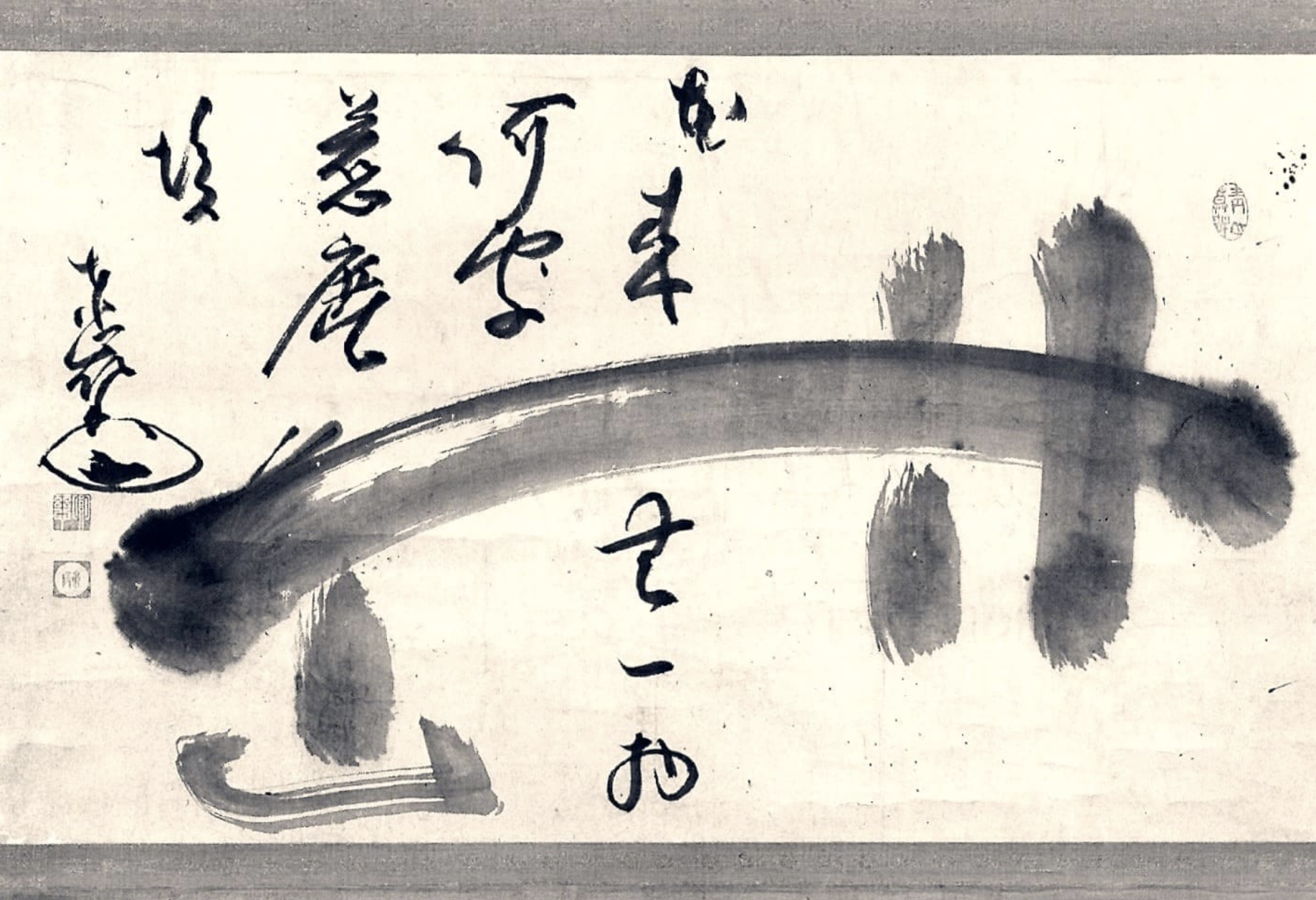

As I noted in the previous post, because we're moving into six-weeks of studying and practicing The Platform Sutra of the Sixth Ancestor, I reviewed some of the scholarly work that's been done in recent years on this pivotal text in the Zen tradition.

See my summary of the problems scholars have with The Platform Sutra here:

I also reviewed what Dogen had to say about The Platform Sutra. Simply put, one thing that modern Buddhist scholars and Dogen have in common is that they both have problems with this text. In this post, I'll dig into Dogen's problems with The Platform Sutra. And set the old dog straight.

First, though, it seems important to note that although Dogen wondered about the authenticity of The Platform Sutra, he didn't wonder about the sudden teaching of the Sixth Ancestor. Indeed, Dogen referred to him as an "Old Buddha," something he reserved for teachers he most highly esteemed - like his own teacher, Rujing, Hongzhi, and Zhaozhou. Further, Dogen mentions "Huineng" about 150 times in Shobogenzo. And he highlights Huineng's sudden teaching particularly in his "Buddha Nature" and "Suchness" fascicles.

In addition, Dogen makes at least several positive references to the contents of the The Platform Sutra in "Universal Recommendations for Zazen," riffing along with Huineng's "don't think good, don't think bad," "making a Buddha," and the "original face." In addition, in his Extensive Record, Dogen cites Huineng directly about 85 times - using events and koan points originally featured in The Platform Sutra.

What was Dogen's problem?

Nevertheless, Dogen didn't like aspects of The Platform Sutra, but what? Surprisingly, he was aware that it had been pieced together over time and he didn't like some of the additions. There were several versions of The Platform Sutra kicking around in Dogen's time, though, so specifically which sections he didn't like isn't clear to us today.

However, we do know that Dogen's primary issue with The Platform Sutra was its repeated emphasis on "seeing nature," 見性 (Japanese, kensho), and a range of related terms that are used repeatedly throughout the text. Importantly, Dogen was not opposed to awakening or talking about awakening (contrary to what many Zennists now believe) - something that I've been writing about for many years. See, for example:

One important piece of evidence in this regard is research conducted by Kokyo Henkel Osho. Kokyo found that in Dogen's Shobogenzo, Dogen used one of the three common characters for awakening 1,155 times. Lordy!

Dogen's most commonly used character for awakening was 證 (Japanese, sho; to verify) which he used 446 times (38.6%). Next most commonly used was 悟 (Japanese, go or satori) which he used 372 times (32%). Finally, 覺 (Japanese, kaku; as in "awakening from a dream") was used by Dogen 337 times (29%) in Shobogenzo.

In contrast, Wansong, a contemporary of Dogen, in his The Record of Going Easy, used one of the three common characters for awakening 304 times (he used other characters as well). His most commonly used character was 覺 (Japanese, kaku; as in "awakening from a dream") which he used 163 times (54%). Next most commonly used was 悟 (Japanese, go or satori) which he used 117 times (38%). Finally, 證 (Japanese, sho; to verify), which Dogen used most, Wansong used just 24 times (8%). Wansong, like Dogen, also used "seeing nature," 見性, (Japanese, kensho) sparingly - only twice in The Record of Going Easy.

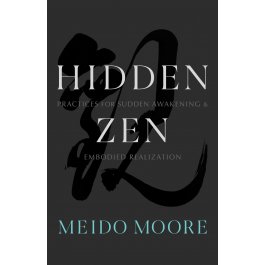

For a modern contrast, and just for fun, I searched Meido Moore Roshi's Hidden Zen. Meido used one of three English words for awakening 235 times (note: Dogen's Shobogenzo is at least five times larger, so Dogen and Meido are in the same ballpark on this). Meido used "awakening" 130 times (55%), "kensho" 100 times (43%), and "enlightenment" just 5 times (2%).

Okay, I may be getting carried away here.

For a condensed (i.e., compared to reading the whole Shobogenzo) version of Dogen's view of awakening, see:

Dogen's problem with "seeing nature"

So if Dogen was strongly positive about sudden awakening and actually talked one heck-of-a-lot about awakening, what was his problem with "seeing nature" in The Platform Sutra? Dogen explains his view in several Shobogenzo fascicles, including "Mountains and Rivers Sutra," "This Mind is Buddha," and "The Monk at the Fourth Stage." Dogen is clear that he doesn't like "seeing nature" because the term makes it seem as if awakening involved a subject/object split between the seer and what was seen, i.e., that true nature is something that is seen as an object of the senses. A fair criticism.

Dogen, by the way, also had an issue with the term "Soto Zen." He didn't use it himself and insisted that what he was about wasn't a sectarian or lineage thing, but just the buddhadharma - the awake truth. Again, fair enough. Curiously, I see many modern Zennists avoiding the use of the word "kensho" like they'd avoid a rabid dog - because Dogen didn't like the term - while they wantonly spew "Soto Zen" with everyone breath - which Dogen didn't like either. So, you modern Zennists, how about some consistency?!

Where Dogen went wrong

What Tetsugan Sensei and I encourage our students to do when studying a text like The Platform Sutra is to set aside preconceptions and personal preferences as much as possible. Then, enter the text and see from within the perspective of the author(s). Critical thinking is also important and necessary to really digest the buddhadharma that's offered, especially by turning the light around to study the self.

In this case, with all due respect (and a lot is due), Dogen seems to have done just that - i.e., he seized upon one term that he had personal issues with and then doubted that The Platform Sutra was an authentic expression of the Sixth Ancestor without (seemingly) considering that it was his own problem.

Dogen was a deeply awakened practitioner and brilliant teacher. And the guy had issues, blind spots, and quirks like all of us. Therefore, to rely primarily on any one great teacher from the past is a mistake for an individual practitioner or a lineage. This mistake has played a primary role in the decline of Soto Zen over the past two-hundred years.

Finally, Dogen may have had a political motivation for disparaging "seeing nature." You see, it was also a favorite teaching term for the Daruma-shu, a Zen lineage in Japan that pre-dated Dogen and from which Dogen recruited many of his followers. One of their essential texts was titled, "On Seeing Nature and Becoming a Buddha" (Japanese, Kensho jobutsugi). Indeed, the Daruma-shu was a frequent foil for Dogen's teaching. In addition, the Daruma-shu had been sanctioned by the government, so Dogen may have had reason to distance himself from them. Many of Dogen's most extreme rants were directed at the Daruma-shu and those esteemed by the Daruma-shu.

It is also possible that Dogen rejected "seeing nature" in order to distinguish what he was offering ("awakening") from what many of his monks believed was the essence of the Zen way based on their previous Daruma-shu training ("seeing nature," aka, "awakening"). Dogen's rejection of the term "seeing nature," then, may have been intended by Dogen as a sudden-awakening move. By reviling a term that his students esteemed (and that was a synonym for terms Dogen used a lot), Dogen may have intended to disrupt his students and trigger an abrupt nondual embodiment.

For Dogenophiles (generally very nice people), more about Dogen and the Daruma-shu here:

Regardless of Dogen's issues, The Platform Sutra has been an essential teaching in the Zen school for twelve-hundred years. Thousands of great Zen masters in China, Korea, and Japan have highly regarded it and many thousands, perhaps millions of Zen students have been powerfully inspired by it. When one of the thousands of great Zen masters thinks that a text is questionable, their opinion should be taken in context and examined closely in consideration with what some others of the many thousands of great Zen masters thought about the text. It would be irrational (and kinda culty) to reject a text like The Platform Sutra just because it didn't sit right with one great master.

What can we conclude from this? Just that Dogen didn't like the term "seeing nature" and even that he had personal issues (and possibly political motivations) with the term that he then projected onto the whole of The Platform Sutra. Bad form, dear old Dogen.

In any case, regarding Dogen's bad attitude about The Platform Sutra, I'd say to him, "Come on, Dogen! 'Seeing nature' is just a term that points to awakening. So get over it already. Of course, the finger pointing at the moon is it too, as you so luminously point out. In any case, old man, lighten the hell up."

Comments and questions are welcome (open to paid subscribers).

Thank you to paid subscribers for your support.